February 14, 2026

Hello,

Aidan and I write fantasy. I love piecing intricate lore together to form a world and peopling it with characters. And Aidan loves crafting a story line filled with battles and wondrous magic.

For example:

But last week, I woke up with a new idea. So I gave myself a vacation from fantasy. Aidan was a little concerned—but I assured him that I can do both. I would take ten days to get the new project underway and then split my time evenly so they both move forward.

I’m going to Machu Picchu with four friends and I’m writing a memoir about it. It’s called Four Old Women Go to Machu Picchu. Will you give the first chapter a read and let me know what you think? I know you’ll probably be reading outside your usual genre, but I’d appreciate any feedback. Let me know if you would be interested in being a beta reader.

Warm regards,

Paula Baker (and Aidan Davies)

FOUR OLD WOMEN GO TO MACHU PICCHU

CHAPTER ONE

I Want to Go to Machu Picchu

216 Days to Go

The group in front wasn’t in a hurry, so we leaned on our drivers and watched them meander down the fairway. It was one of those lazy golf‑course mornings when the biggest decision you face is which club to use.

“Holly wants to go to Machu Picchu,” Jen said.

“I want to go to Machu Picchu,” I replied.

Where had that come from? Until that moment, Machu Picchu existed somewhere between grade six social studies and postcard fantasy. Had I ever given it any real consideration?

Maybe it was turning sixty, or maybe it was simply my rule never to say no to a good opportunity—but something in me sparked. Machu Picchu felt like the obvious next thing to say yes to.

Blame the group ahead for making me wait. Idle me is dangerous—I’ll grab onto an idea and run with it all the way to the Andes.

Holly and Jen are my hiking, skiing, and golf friends. After I retired, I went looking for people who would go outside and play with me. I knew Holly from librarian meetings, so I called and asked her to join me for a round of golf. She readily agreed—and when I asked about anyone else who might be able to join, she suggested Jen.

The women I had been playing with cared passionately about the game. They dressed in fancy golf clothes, matched their bags to their shoes, had sparkly ball markers, and knew every rule in the book—but I was really only there for the walk.

I had a couple of rules for anyone joining the crew I wanted to put together. First, they had to agree to play ready-golf, so we weren’t always waiting around for etiquette reasons. Second, they had to be willing to ignore my flouting of the rules—I just want to whack and walk. And finally—no skorts.

They both agreed to my crazy rules—and then Jen broke the skort rule almost immediately. She’s a fashionista who loves to shop. Holly even showed up one day in a borrowed skort—just because she could.

What was I going to do? Kick them out of my meticulously curated three-woman golf league? The skort rule fell by the wayside.

Jen has been attempting to teach me to swear. When she hits a poor shot, she can blister the air. It’s a fantastic skill for a former kindergarten teacher. I’ve never mastered the art. Besides, when I miss-hit, my impulse is to laugh. If I look up and see that ball skying off in the wrong direction, it tickles my funny bone. It’s hard to laugh and remember to inject some profanity at the same time.

I’d tackled more than one adventure with Holly and Jen. There was a trip to Nimpo Lake in Northern British Columbia with six other women—two of whom were twenty years older than me.

We paddled the Turner Lake Canoe Circuit during a summer so dry we spent more time carrying the canoes than sitting in them. Back and forth we trudged along the portage route, hauling the wildly optimistic gear we’d packed, along with those monster boats—and wishing for wheels every sweaty step. Six bags of potato chips in a backpack? Featherlight. The mosquito‑net tent with the mass of a small car? A whole different story.

At our first campsite, we ate chips and drank the wine Holly had decanted into her Camelbak. By standing waist-deep in the lake, she could keep it chilled—and cool herself at the same time.

Then we moved on to Hunlen Falls, the third-tallest single-drop waterfall in Canada—and the mosquitoes declared war. That absurdly heavy net tent became the most valuable thing we’d brought.

After Nimpo Lake came a hut-to-hut hike in Wells Gray Park, where we slept on real mattresses and ate hot dinners cooked by our young guide, while congratulating ourselves on choosing a trip with real bathrooms.

The year after that, we flew by helicopter into the Valkyr Range and stayed in a lodge built by our hosts. Each morning, we packed our lunches and followed Martin up whichever peak he felt like climbing, while Shelley stayed behind and worked miracles in the kitchen.

It was strenuous and spectacular—and it convinced me that it was the sort of thing I should keep doing forever—or for as long as I can.

When the foursome ahead finally moved out of range, Jen lined up her shot, gripped her driver, and swished her skort. “Let’s do it,” she said as she stared down at her little pink ball. “Let’s go to Machu Picchu.” Then she crushed her shot down the middle of the fairway.

That was it.

After golf, I went home, pulled out my laptop, and started a conversation with AI. “I want to go to Machu Picchu with my friends,” I said. “We are all over sixty.”

The answer was completely unacceptable.

It suggested a train to Aguas Calientes, a bus to the entrance, and several gentle senior circuits where we could stroll and rest at our leisure—as though Machu Picchu were a shopping mall with benches.

What?

Being over sixty didn’t mean I was elderly. Did it?

I tried again. “We are strong, fit, and experienced hikers. We don’t want to take a bus.”

That’s when I discovered Wildland Trekking, a company that takes care of everything—except tying your boots for you. And honestly, I’m not convinced they wouldn’t help with that too.

You get a guide who knows the trail, the terrain, the altitude—and every ruin along the way. They handle the hotels, restaurants, buses, trains, permits, tickets, and schedules—the sort of mind‑numbing logistics I consider a waste of my remaining lifespan.

A chef accompanies every tour. More importantly, they include snacks. Holly and Jen can attest that snacks are my favourite part of any day. When you’re hiking, it’s the little meals between the big meals that make it special.

The tour takes care of water, filtering it, boiling it—and possibly even blessing it. Whatever it is, we won’t be getting sick.

Porters haul most of the gear and food. We get a small pack—just enough to feel as if we’re actually hiking—but only ten kilograms (twenty pounds). Compared to what we normally haul through the B.C. backcountry, it sounded like a piece of cake. And really, having people carry our things is the closest we’ll ever get to being Downton Abbey’s Upstairs People.

According to the website, the porters reach camp ahead of us and will have the tents set up and waiting.

That little tidbit gave me pause. Would we stagger in behind them, wheezing and pretending it was because we’d been admiring the view?

How hard was this trip?

But if anything, that only made it even more appealing. It’s not fun if it’s not a challenge. Right?

Having made my choice, I proposed it to my husband. He declined immediately. He’s an avid outdoorsman who’s hiked many of British Columbia’s trails, and although we still cycle and kayak together, he no longer enjoys hiking because it hurts.

His answer was generous:

“Ask the crew,” he said. “Someone will go with you.”

It wasn’t that I needed his permission. I’d been hiking without him for years. But this was different. It was South America—neither of us had ever been there.

I’m terrible at geography. I couldn’t have pointed to Machu Picchu on a map. I didn’t even know it was in Peru—let alone where Peru was, that Lima sits on the ocean, or that Cusco, the jumping‑off point for the Inca Trail, is in the Andes. I hate to admit that I may have pictured the Inca Trail like the Yellow Brick Road.

Altitude was another blind spot. Growing up on the prairies of Manitoba, I didn’t see a mountain until I moved to B.C. when I was twenty‑four. I had no idea that the summit of Apex Mountain, where I ski all winter, sits around 2,178 metres (7,146 feet). Cusco, where our trek would begin, is much higher at 3,400 metres (11,152 feet). And the highest point on the Inca Trail climbs past 4,200 metres (13,779 feet)—into air thinner than anything my lungs had ever encountered.

I’d heard Holly’s story about getting altitude sickness on Kilimanjaro. It sounded dreadful—she lost an entire day and remembers none of it. Somehow, I did not make the connection.

I also forgot that I have mild asthma, which likes to announce itself at altitude, and that I’m no longer in love with sleeping on the ground. I didn’t think about the diseases my tidy North American immune system has never met, or the cost of travel vaccines.

I didn’t even think very hard about the price. It was listed in U.S. dollars, and I didn’t bother converting it or factoring in airfare or the extra days we’d inevitably tack on—because let’s face it, when would we ever be back in South America?

Ignorance, as it turns out, is a remarkably effective planning tool.

With Doug’s approval, I looked at the calendar, picked a date that did not interfere with our other trips, and sent a message out to a dozen hiking buddies. The replies came in quickly—some had already been there and enthusiastically recommended it. Others decided it was at the wrong time of year, too hard, or too expensive—which were all very fair points.

Holly was in immediately. Jen too. Margie was the last to jump aboard.

She’s been my closest friend for thirty-five years, ever since we taught in the same school. During the initial investigation of the trip, she was in Australia, visiting her daughter—so she was blissfully short on details. In fact, she did not even glance at the website—she was too busy having the time of her life.

I was careful. I didn’t push. I suggested. I reminded her there were deadlines. I said it was fine if she didn’t want to do it.

But Margie is not one to miss out—especially if her husband calls it an opportunity too good to pass up. So, without knowing anything beyond the destination—and without fully considering that her psoriatic arthritis medication leaves her immunocompromised—she agreed.

It was all we needed.

Four people was the perfect number for travelling. The trip stopped being an idea and became a commitment. There were flights to book, permits to secure, vaccines to get, equipment to buy, bags to pack, and 206 days to figure out where we were going. We had the crew, the date, and the destination.

What could possibly go wrong?

Let me know what you think.

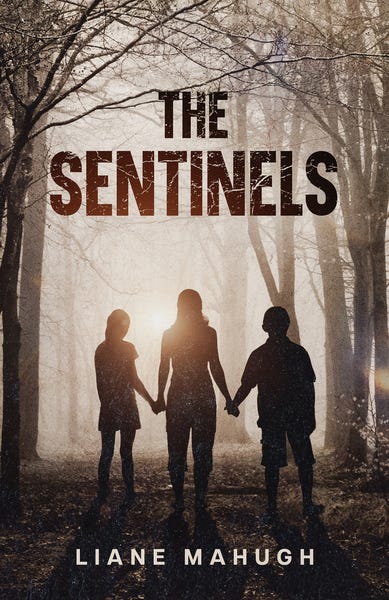

P.S. The Sentinels by Liane Mahugh is on sale now.

Three kids - three mysterious trees - one unforgettable summer. A Supernatural Coming-of-Age novel.